The guest for this Episode is Ros Schwartz.

Ros Schwartz is an award-winning translator from French. Acclaimed for her new version of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, published in 2010, she has over 100 fiction and non-fiction titles to her name. She is one of the team that has retranslated George Simenon’s Maigret novels for Penguin Classics. Her recent translations include Swiss-Cameroonian author Max Lobe’s A Long Way from Douala and Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside, a new translation of Simone Weil’s The Need for Roots and, in a very different vein, a manga version of Camus’ The Outsider.

Appointed a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2009, in 2017, she was awarded the UK Institute of Translation and Interpreting’s John Sykes Memorial Prize for Excellence.

(00:00) Introduction to the Guest: Rose Schwartz

(01:33) Rose Schwartz’s Early Love for French

(03:29) Living in France: Experiences and Learnings

(04:37) Entry into Translation

(06:48) Challenges and Triumphs of First Book Translation

(12:48) The Art of Translation: Balancing Meaning and Music

(15:54) Engaging with Authors: Building Trust and Understanding

(18:05) The Role of Editing in Translation

(23:03) Reading for Pleasure vs. Translation

(23:58) Evaluating Translation: A Complex Process

(25:48) The Art of Mentoring in Translation

(27:54) Pitching Translations to Publishers

(32:03) The Impact of the Writers in Translation Program

(35:06) Exploring Personal Themes in Translation

(36:19) The Meaning of Translation

(37:00) Current Projects and Future Endeavors

(38:02) The Power of Co-Translation

(42:18) About the book -Translation as Transhumance

(47:28) Closing Remarks

Transcription:

Harshaneeyam: Welcome to our podcast, Harshaneeyam.

Ros Schwartz: Thank you very much for inviting me. It’s a real pleasure to be here.

H: Number of books you translated from French, I think it’s more than a hundred right now.

Ros Schwartz: That’s correct.

H: So when did this love affair with the French start?

Ros Schwartz: It started in the cradle. My parents were both Francophiles, and they loved French music. They played songs by Edith Piaf, Charles Trenet, and Tino Rossi, and that was the soundscape of my childhood, of my babyhood.

So I was exposed to French, from the womb, practically. And my parents, if they didn’t want me to understand them, they would speak to each other in French. Of course, I made it my business to learn French. And I have to stress this was very unusual for the 1950s in the UK. People didn’t travel so much. It was very unusual to be brought up by parents who spoke French. And my mother had a French penfriend who was a school teacher. She was like a sort of caricature of the French school teacher. She used to come and stay, and she’d blow around the house, expostulating in French. When I was 15, I was sent to stay with her family. She didn’t have children—her sister and her husband, who was a butcher, had five teenage kids, and I went to stay with that family. And I think that was really my baptism of fire into French because they would tease me mercilessly if I got things wrong, and they taught me all sorts of unsuitable expressions. So, for me, French was just part of my DNA, and When we started studying it formally at school at the age of 11, for most people, that was something completely new, scary, and terrifying.

For me, it was just a continuation of what I already did. And I went on to study French at university. But I wasn’t cut out for academia, and we didn’t get on. So, I did what it was fashionable to do in the early seventies. I dropped out, and I ran away to Paris. And. It was the year that the UK had just joined the EU. So it was very easy for me as a British person to get jobs, to live my life. I went to university in Paris. And I did all sorts of odd jobs. I was a telephone operator on the French railway at the information call centre, and I think there are probably people still wandering around France today looking for the train to Bordeaux when I’d sent them somewhere else. I worked on a goat farm in the south of France. I’d picked grapes and learned a lot about wine. I didn’t realzie at the time that this was the best possible training for a literary translator. Because I was exposed to different registers of language spoken by different classes of people in different situations. So, really, it’s been a lifelong love affair with French.

H: Getting into translation, how did it happen?

Ros Schwartz: Completely by accident. When I lived in France, I was teaching English in companies. It was a very easy way to make a living. And I wasn’t really thinking about what I’m going to do when I grow up. I was just living my life. Earning enough money to get by. But towards the end of my stay in France, I came across a book I felt I had to translate. And without knowing anything about translation or publishing or how anything worked, I translated it. And then I hawked around for five years until I found a publisher. In the meantime, I came back to the UK at the age of 29 and found out that I was completely unemployable because I had no employment history.

I had no office skills. I remember going into employment agencies, and they’d say, what are your speeds? And I had no idea what they meant. They were talking about shorthand and typing. I would apply for all sorts of jobs, and I’d very often get an interview, but the prospective employers thought I was too old to go in at the very bottom level but I didn’t have any experience of working in this country to go in at a higher level.

Having realized that. No one was going to employ me, and I needed to earn a living. I literally launched myself as a translator. And in those days, there was no translator training. There were no university courses. People were pretty uninformed about what translators did. And the fact that I knew French and I lived in France and I said I’m a translator, people gave me work. And astonishingly, I gradually built it up from there. So, I learned on the job. And that’s one of the reasons I’m so committed to translator training now, because I would not like anyone to have to go through what I went through to learn how to be a translator.

H: Well, how did it get published, your first book?

Ros Schwartz: I just wrote to publishers and presented it and pitched it, and eventually, I found one thanks to sheer perseverance.

H: So what is the title of the book, and who is the author?

Ros Schwartz: It’s called ‘I Didn’t Say Goodbye’ by Claudine Vegh.

H: How about the reception for the book?

Ros Schwartz: Difficult to say. I don’t think I even had a contract.

I certainly didn’t receive any royalty statement. I have no no idea. But it was recently republished by a publisher in America. It’s a series of interviews with Jewish people who were children during the war and whose parents perished in the camps, but they somehow managed to save their children. So, these are individual accounts of what that experience had represented for them. The fact that they had lost their parents to sacrifice themselves for them to survive left them with very mixed feelings, Gratitude, anger at their parents for having allowed themselves to be carted off. It was a very deeply moving book, which really spoke to me, and I just felt I had to translate it.

H: So in your translation career in the beginning years, can you recall any watershed moment, a person that whom you have met, a translator or somebody, something really you think which made you take off as a translator?

Ros Schwartz: As I said before, I had no training. I had no idea really what a translator was supposed to do. I was groping in the dark and working intuitively. And just as I was starting out, the translation profession started to become organized. The Institute of Translation and Interpreting had its first conference, and I went to that conference; there was a professor from France, Professor Danica Selescovitch, who was a great name in the translation world, and she gave a talk. And in her talk, she articulated all the things I’d been intuitively working towards. So hearing somebody actually talking about translation and putting into words what I was doing, I think, gave me a kind of confidence and boost. This was the early 80s.

H: Almost 43 years ago…

Ros Schwartz: Yeah, don’t remind me.

H: Now, when it comes to French, French translated literature,, French is spoken in many, many different countries. In Africa, of course, in France and some places in Europe too. So, the books that you have translated must have come from different countries, right? Obviously, there must be some variation in the way French is spoken in different parts. How do you handle this, actually? And is there any way French comes from a specific region? You make the reader understand that it is a different sort of French when you translate. Do you make that effort?

Ros Schwartz: A lot of the writers from North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, write in the French of France, and they are published very often in Europe, and they are writing to reach a European readership. So a lot of them write a French that is very much the French of France. This is the legacy of colonialism, it’s almost to prove they can write as good, if not better, French than the French. So, it’s not really a problem in that these are books that have been published by French publishers. There is one writer whom I translated, Max Lobé, who is from Cameroon. Although Max, is Swiss Cameroonian, he writes in French, he’s published in Switzerland, and he writes very much with the European readership in mind.

But, in one of his books in particular, A Long Way from Douala, he uses a lot of Camfranglais words. Now, Camfranglais is a kind of urban slang that is a mixture of French and English because Cameroon is a bilingual country and has local languages. He works these words into the French in a way that the French reader will understand them.

So, he knows that his readership is European and he uses Camfranglais words so that in this context, you understand them. I keep those. And that’s what gives the book its particular flavour. Quite often, they’re onomatopoeic expressions. Things that, you know, you don’t know exactly what it means, but you get that this person is surprised or angry or whatever. So, I would say that Max Lobt is really the main one who writes in what I would call a non-standard French. I haven’t translated anything that’s published, say in Africa, that is written for an African readership.

H: The sonic quality of French is quite different from English. How do you handle it?

Ros Schwartz: Okay, that’s a very good question. Translation is a continual juggling act between meaning and music. There are specific texts where the meaning is paramount. If you’re translating a legal document, then you’re not worried about the music. At the other end of the spectrum, you have poetry, where the music is paramount. And meaning sometimes has to go out the window in order to create the poetry. Most prose texts are somewhere on that spectrum. And so you’re continually having to weigh up meaning versus music. And I think the book that brought that home to me the most was when I translated Saint Exupéry’s The Little Prince, which, on the surface of it, is a short children’s book. It’s very simple language.

And I thought, Oh, this is going to be very straightforward to translate. But I found once I’d done a first draft that where the French is light and airy, the English was clunky. I’d been translating, as I always do on the first draft, I’d been translating for meaning. I wanted to make sure that my English said what the French said. But when I started reading it, it was catastrophic because it went clunk, clunk, clunk, clunk. And the French were just beautiful and airy. So, I enrolled my daughter, who is very musical. She plays several musical instruments. She has perfect pitch. And I would read the translation to her out loud. And she would just listen with her eyes closed. And every so often she’d go, Ah, ah, ah, ah, ugly, ugly, ugly, ugly, ugly. And so I would say, okay. And sometimes, it was a question of making an alliteration or using a two-syllable word instead of a three-syllable word. We read it to each other over and over. I read it to her, and she read it to me. And by that point, I had the meaning, I knew it was accurate in terms of meaning. We were just listening for the music, and listening to somebody else read your translation, you hear it in a different way. And that was where the actual work was on this particular book. And it’s a lesson that I took with me for everything I’ve done since, which is, you know, as a translator, you can get too obsessed with meaning and forget about the music.

And I think that’s where a lot of translations fall down. We’ve all seen translations that are completely accurate, they’re grammatically correct, they make sense. Somehow, they’re not a pleasure to read. So that’s where, and working in English, it’s such a rich language, there are always so many options. But if something’s not working, you can play with it and find another word that’s lighter or alliterative or play with the word order in a sentence.

H: You must have engaged with writers, too?

Ros Schwartz: Yes. So, some authors want to be more engaged than others because, by the time you’re translating a book, it might’ve been published two or three years ago. They’ve moved on. They’re somewhere else. And you ask them a question. And they’ll say, I have absolutely no idea what I was thinking at the time. So what I usually do is when I’m commissioned to translate a book and the author’s alive, I get in touch with them and introduce myself and say, I may have some questions for you. How do you want to be contacted? I won’t contact you till the end. Do you prefer email, phone call or whatever? And I want to gain their trust. There’s nothing worse than a writer who doesn’t trust you and starts interfering in the translation because they think you’ve got it all wrong. So I try to build that relationship at the beginning.

I try to go and see them if possible. And some of my authors have become really good friends. Others are not particularly interested. If they know English, They’re more engaged with the process, which can be a plus and can also be a negative. There’s one author who shall remain nameless, who would start questioning things and say, but I want to say it like this, and I’d say, you can’t say it like that in English. And then she’d go and ask 20 of her English native-speaker friends, who’d all say to her, no, Ros is correct, you can’t do that. And she’d come back and say, okay, we’ll do it your way. But after that initial teething period with her, she learnt to trust me. And now she trusts me completely and doesn’t do that unless there’s something that she really feels doesn’t work, and she’ll say to me, this isn’t quite what I mean. So that’s fine. It’s wonderful to have an author who first trusts you, isn’t afraid to point things out, who engages with the process and who understands what that process is, and why you make certain decisions.

H: And when it comes to editing the translations, what has been your experience?

Ros Schwartz: Where do we start? So, I think editing translations is something that doesn’t get talked about. Funnily enough, I had a conversation the other day with somebody who runs an editorial consultancy and does workshops. And I was suggesting to her to do a workshop on editing translations specifically because. I think what’s complicated is that when an editor is editing a translation, they sometimes forget that there’s an original author and that different countries have different editing traditions. So when you’re translating from some languages, the original hasn’t been edited, and so the English publisher will pick up on things that are nothing to do with the translation. So they might say, Oh, this is way too long. We need to cut about a third of it. But that’s beyond my pay grade. I’m a translator. I can’t say we need to cut a third of it. If an author makes very specific choices, say, around punctuation, they decide not to use quotation marks for speech or something like that, as the translator, you’re going to replicate that. They’ve done it for a reason. You do that, and then your publisher says, Oh God, you don’t know how to use punctuation properly.

And a lot of it comes down to communication. As a translator, I try to preempt what I know editors are going to pick up on, and I put in a note, I’ll say, by the way, this author doesn’t use capital letters, whatever. So, you try to preempt what you know editors are going to pick up on. Or if there’s, say, a pun in the French, that’s just not going to work in English. Can’t make this work in English, but I’ve got to pun three pages later where there isn’t one in the French. I think it’s about dialogue and the right chemistry between the translator and the editor. The perfect editor doesn’t intervene unnecessarily, but saves you from yourself. So if you’ve done something really daft, they’ll pick it up. You rely on them for punctuation, spelling, and stuff like that. But what I appreciate is the editor who says. I found this sentence a little bit difficult to follow. Could you have another look at it? So, who doesn’t rewrite your translation as some editors have done in the past? And that’s partly because they haven’t been properly briefed.

So you have an inexperienced editor in a publishing house, and the publisher says, here, can you edit this translation? With no brief, no idea what they’re doing. I had one who would query words because she didn’t know what they meant, even though she worked in a publishing house that published dictionaries. And, I’d say, why have you queried this word? And she said, well, I don’t really know what it means. Or another one who would substitute words. And you say, why have you put this? And she said, well, I thought it sounded better. But that’s not what the French said. So, a lot of education needs to go on with editors. And I believe, in a way, editing has become a victim of what’s happened over the last couple of decades in publishing, where you used to have in a publishing house very experienced editors who would train up the next generation and who worked on paper so that there was a sort of a trail. When new technology came in, publishers got rid of that whole layer of editors because they refused to work on computers. They said, no, no, no, I’m not just going to whack this through a spellchecker. I’m going to sit down and carry on. in the way I’ve always done, which is on paper. So the publishers got rid of that layer of editors and brought in whizz kids who knew how to use a computer and put something through a spellchecker, but had no experience or basic culture or knowledge. And they would do things and not use track changes or anything. So you couldn’t actually see what had gone on. And I’d get proofs back of a book I’d translated, and I’d start reading the proofs and thinking, I didn’t do this. This isn’t my work. And there was no trail as to what had gone on. So yes, editing requires huge sensitivity.

H: Now the other interesting part for me, for a senior translator like you, you must be reading some books with an intention to translate. And there are books you probably read for pleasure or How does the experience differ? Do you look at both in the same way or differently?

Ros Schwartz: I think reading for pleasure gets harder and harder because if I read a French book, I’m translating it in my head, and I’m thinking, how on earth would I translate that? So when I read French, I’m always wondering whether I would want to translate it, how translatable it would be, how difficult, et cetera. And when I read English, I’m reading it with an eye on the language: Oh, that’s an interesting word. Oh, that’s a good way of saying things. Oh, I must, I must use that sometimes. So a book has to grab me for me just to get lost in it for pleasure.

H: What is your process of evaluating translation?

Ros Schwartz: Oh my God. It’s scary in a way because when you’re judging a prize, you’re looking for a very good translation of a very good book. You might have a very good translation of not such a good book, or you might have a not very good translation of a very good book. And these things are all slightly subjective. So there are books you like and books you like less. And when you don’t like a book very much, you think, Is this me? Am I missing something? Have I not understood it? Am I being harsh? It’s hard to trust your own judgment. But I think what was interesting with the Saif Ghobash Banipal prize was that we were four judges, two who knew Arabic and who read the book in Arabic and English, so they were really judging the translation based on the Arabic, and two of us who don’t know Arabic and who were just reading the English and going with our gut feeling on the English. And when you’ve seen a lot of translations, you get a kind of sense of when something’s gone wrong in the translation, when something’s not working, unless you’ve missed some major thing. It is a very good translation because it’s compelling as a book. And the four judges all came to more or less the same conclusion, both for the winner, which we were unanimous about, and the shortlist. We each read the books and produced our shortlist. And we were all on the same page, which was very reassuring because it means that something shines through.

H: And you must have mentored many people over the years. Tell us about some interesting experiences.

Ros Schwartz: I think the exciting thing about mentoring is it’s also a form of professional development for oneself. When you’re working with somebody else on their translation, You have to think about and articulate your own practice. You can’t just say to somebody, oh, this works, or this isn’t very good. This doesn’t work. This would be better. You have to unpack it all and say why and what’s the process. So, I think I see mentoring in two ways. One is partly as a midwife, and you’re helping that person give birth to what’s inside them. And. I think what is lacking in a lot of people when they’re starting is confidence. And quite often, translators will pull back. So they’ll do a translation. They’ll cling much too closely to the original because the big question is, am I allowed to do this? And there’s nobody to say you are or you aren’t. You have to, as you mature and gain confidence, you have to have the courage of your own convictions. And so, yes, I am allowed to do this because I think it works. And they’ll be people who disagree with me. And there’ll be people who agree with me, but this is my translation, and I’m taking ownership of it.

When people are starting out, they’re afraid to do that, so they’ll sit on the fence. As a mentor, you can encourage them to go in the direction that they want to go in, but they’re pulling back. And so many times I’ve said to a mentee, how about this? And they’ll say, oh, but that’s what I had originally, but then I changed it. So helping give birth to the brilliant translation that’s inside them. And it’s also, I think, a way of making you constantly think about what you’re doing.

H: Pitching to the publishers, do you have any suggestions for translators?

Ros Schwartz: Yes. I think that, first of all, it’s a perfect way for people to start, because when somebody’s starting out it’s no use writing to publishers saying, Hi, I’m a translator, got any work? But to pitch positions you as someone who’s got their ear to the ground, who knows what’s going on in the language that they translate from, and as somebody who’s proactive. And publishers do not have time to read everything that’s published everywhere. So they, I think, are increasingly, and I’m speaking about the English language publishing market, publishers are increasingly open to pitches from translators, provided translators do it professionally. And that’s something we do a lot of training in at Bristol Translate Literary Translation Summer School. We try to educate translators on how to pitch. And I think that the biggest shock that they have to get over is that publishers are commercial animals and they’re thinking about the market, and translators tend to say; this is an amazing book. It’s beautifully written. It’s exquisite. And a publisher sitting there thinking, and who will buy it? And how many copies am I going to sell? And how am I going to pitch this to my salespeople? So, a lot of pitching is about translating your passion into publisher-speak. Say, okay, here’s this fantastic book and publishers will say things like so is it more like Dan Brown, or is it more like Joanne Harris? You have to hold their hand because they need an English book as a sort of yardstick. You say, Oh, it’s a Hindi Dan Brown. Or whatever. So that they can, in their heads, position it in the market. And then they’ll say things like, Would you buy it for your mother-in-law for Christmas? Again, thinking market, who’s going to buy my book? And then they ask questions about the author. If you’re pitching for a foreign book, does the author speak English? Are they marketable? Can they do events? And it’s something, and I know that there are different cultures around this in other countries, but in the English-language market, authors are expected to do festivals and events, and authors who don’t speak English and will never come out are less marketable. So there are all these things that we must bear in mind because that’s what the publishers have in mind. But I see more and more is translator-led projects coming to market because I think, as a profession, we’ve matured; we’re seen as grown-ups at the table. No longer these sort of little creatures waiting for the crumbs to fall from the table, but we are part of the conversation. And we’re seeing more and more books that have been instigated by translators winning prizes, and it’s often the small independent publishers that are picking these up and getting on the prize list.

And even translators who’ve set up publishing houses. So I think that pitching if you go about it in the right way, is a meaningful way. And I believe that’s how Tomb of Sand, which won the International Booker, started as a pitch. But I know it was Arunava Sinha who helped the translator bring it to the press. So, I think translators have an active role to play in beating down the gate and challenging the gatekeepers.

H: Before we get to your work, your association with the English PEN’s Writers in Translation program. Can you take us through that?

Ros Schwartz: The Writers in Translation program started in 2005, and it was one of those extraordinary things. Bloomberg, the big news agency, contacted English PEN. And said, we’ve got all this money, and we’d like to spend it on translation. It’s hard to believe, but I think one person at Bloomberg who had a budget and was passionate about translated literature.

So PEN thought, Ooh, wow. And there were no strings attached. It was like, we’re going to give you this money. You use it for translation. PEN set up a committee to figure out a programme and how to spend this money the most effective way, and that’s when there were two strands, one of which was PEN Promotes because one of the things that was identified was that it’s all very well a book being translated, but if publishers don’t have a promotional budget, the book just disappears. So there was the PEN Promotes strand, and then there was the PEN Translates strand, which funded grants for the actual translation. And I was involved right at the beginning with that committee. That partnership ceased, I don’t know quite when it was, but in the meantime, the Arts Council of England, which is the body that funds – it’s really the only government body that funds literature, the Arts Council realized they didn’t have the in-house expertise, and they started outsourcing quite a lot of their programme.

They asked PEN to take over the budget for funding translations. So PEN set up the committee, and that committee continued, and at that time I was chair of the committee. So we developed our programme, which is now PEN Translates, and I worked with Emma Cleave, who was then PEN’s translation programme manager. So Emma and I devised the programme that we now see, which has gone through a few changes and amendments, but basically, I was the architect with Emma of that programme.

H: So, how many translators might have benefited from this program?

Ros Schwartz: Each round, there are two rounds a year, and each round funds about 30 to 15 books, about 30 books a year. Well, initially in 2005, so it’s nearly 20 years.

H: Yeah. Twenty years multiplied by 30, about 600 books.

Ros Schwartz: Something like that, if not more. And these books would not exist if it hadn’t been the funding from all sorts of languages that have never been translated before. More publishers who wouldn’t be able to afford to do the books. It has changed the landscape of what gets published in English.

H: Coming to your work, back to your work, are there any themes that you think that you are specifically drawn to?

Ros Schwartz: I thought about that question. I believe that the word I’m looking for is empathy. So I don’t say, Oh, I want to do books about this or books about that. If a book speaks to me and if it aligns with my own passions and interests, then I’m interested and I like variety. I like change. So I don’t limit myself by saying, Oh, I’m only interested in books by women, or I’m only interested in books about this. I’m interested in a book that has some indefinable quality that speaks to me. As I said, I like new challenges. I like variety. I’m open to suggestions. I’ve just done a manga version of Camus’ The Outsider, which was something completely different for me. There’s nothing that I’m driven to seek out.

H: You had a very successful and fruitful and long career in translation. What does it mean to you?

Ros Schwartz: What does it mean to me? My home. It’s my way of being in the world, and it’s not just, it’s not just what I do as a job. You’re translating all the time. When you speak to another human being, you’re translating what you think they might be saying, what’s behind the words, and what the emotions are. Translation is my life.

H: That sentence will do… No need for any further explanation. What is that you’re currently working on, Ros?

Ros Schwartz: A book by a Moroccan writer called Khalid Lyamlahy. And it’s called, I haven’t got an English title for it yet because I haven’t started translating it, but called translates as. ‘Evocation of a Memorial in Venice’ and it’s a novel where he imagines the back story of a refugee who commits suicide by throwing himself into the Grand Canal in Venice. And he’s a witness to this. And so he imagines the journey of this man, how he came to this point where he threw himself into the canal, what he’d been through. And it’s a way of humanizing what has become statistics.

H: I have picked up two books to talk to you about. One is … ‘About my mother’. Interestingly, you are involved in co-translating the book.

Ros Schwartz: The book is by Tahar Ben Jelloun, and it’s called a novel, but it’s very autobiographical, and it’s about his mother dying of Alzheimer’s. So it’s a very personal memoir and part of it is him talking about his reaction to being with his mother, and part of it is imagining himself inside her head, so that’s the novel part of it.

The co-translation was with Lulu Norman and Lulu’s someone I’ve collaborated with and co-translated with several times. We first collaborated because there was a book she had found that she was very keen to translate, a book by an Algerian writer called Aziz Chouaki called The Star of Algiers. And she’d taken it to a publisher who sat on it for months and then came back to her and said, yes, we’re going to do it. By that time, Lulu was no longer available. And she very generously suggested me, but I knew she really wanted to do it. So I said, why don’t we co-translate it? I happened to be available at that point. I said, I can do the first draft, then you can come in. And I think neither of us at that point had realized how valuable co translation can be. What we discovered is we have very different strengths and weaknesses. So, parts that I struggled with were easy for her. Parts that we both struggled with, we were able to brainstorm over. And I think it’s also having somebody who’s in there as deeply as you are, much more than an editor because we were both absolutely inhabited by the book. But co-translation isn’t a given. You have to make sure that you work with somebody with the same sensibility. And you can’t have any ego because If Lulu commented on something I’d done, it wasn’t a question of I liked what I did, and I agree with you about that. It was about what worked best for the book. So I think the book, the translation, was a thousand times better than it would have been if I’d done it on my own. Because we pushed each other to go further, one of us would come up with half a solution, and the other would say, yep, do it, go for it. One of the hardest things about that book was the punctuation because Chouaki writes long sentences punctuated by commas. When I’d done my draft, I’d gone with the French and done the same thing. And Lulu was quite rigorous, and she said, no, that doesn’t work. We’ve got to have full stops because he’s a jazz musician. The book had a particular beat, and to get that beat in English, it taught me a lot about punctuation. So, I think co-translation is a form of continuing professional development. Humbling because it’s a reminder that a translation can always be improved. And that there’s no one way of doing things.

And again, that’s something that comes out of workshopping. You have a text that you think you’ve cracked, and then you’ve got six people in the room, and they all come up with a different way of seeing it. I think we need to always remind ourselves to slow down, think, and remember that there are other ways of seeing something that might be ambiguous. So, having done that book with Lulu, we then did another book together: ‘The Belly of the Atlantic’ by Fatou Diome, the Senegalese writer. And again, that was a question of time. One of us was available. The other wasn’t. I think it was the other way around this time. So Lulu did the first half. I did the second half. We swapped over. And again, the book benefited. So when Tahar Ben Jelloun came out, we just thought we’d do it together because we like working together.

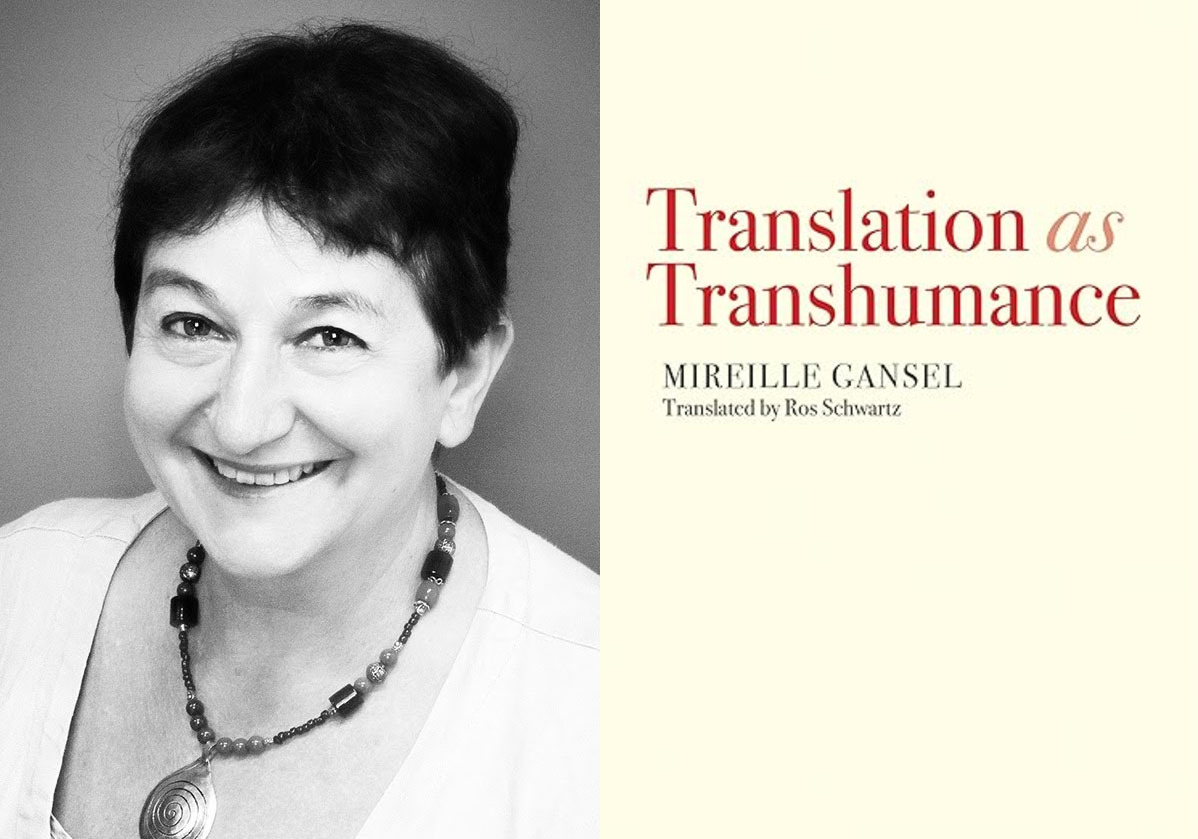

H: The other one, which I just received a copy is ‘Translation as Transhumance’.

Ros Schwartz: Translation as Transhumance is by Mireille Gansel, who’s a French writer, who’s also poet and a translator. The thing about Mireille Gansel is that she has lived her entire life through her commitment to bringing the voices of persecuted writers into French. She translates from German, so during the Cold War, she used to go to Eastern Europe and seek out persecuted writers, East German writers, and translate them, taking a significant personal risk going to East Berlin when the Wall was still there.

And then I think the most extraordinary thing she did was when the Vietnam War broke out, she thought, okay, what can I do as a writer and a poet? I can’t stop the bombs, but I know I’ll go to Vietnam, and I’ll translate Vietnamese poetry. In the middle of the war, she went to Vietnam. She learnt Vietnamese. She brought the voices of the Vietnamese poets into French. So, there is a kind of integrity about the way she has lived her life. This book, Translation as Transhumance, likens the act of translation to that of the practice of transhumance, which is something that in Mediterranean countries, shepherds take flocks of sheep to the richest pastures. In the summer, they take them up the mountains to the high pastures; in the winter, they bring them down. And there are pathways across Europe, transhumance paths that don’t respect national borders. This idea of taking flocks of sheep across different countries and the hospitality that entails, she likens to translation, the act of translation. And this book, I think of all the books I’ve done; this one has a very special place in my heart. This book moves me. It was sent to me by a friend of Mireille’s, Nick Jacobs, a retired publisher. And for some reason, he sent it to me and I read it in one sitting. And I said this to Mireille: I had the feeling that this book was written for me to translate, which sounds incredibly arrogant. I had to translate it. So, I found a publisher for it. I don’t know if you’ve got the book, the edition that has my afterword in it. It’s a kind of memoir, but it’s a mosaic memoir. And there are different parts of her life. She always relates it to translation; at the end of each chapter, there’s a little aphorism about translation. And really, it’s the book I wish I’d written.

H: Please read a paragraph from the book.

Ros Schwartz: Mireille has gone to visit the French poet René Char. And she’s been to see him because when she was in Vietnam, there was a Vietnamese poet who was an admirer of René Char, who’d asked her to bring back some of his poems. And René Char lived in Provence. So she visited him, and Char gave her some of his poems for this Vietnamese writer.

I left with those treasures in my bag – or rather my shepherd’s satchel, because that little Provencal road made me think of transhumance – the long, slow movement of the flocks to distant places, in search of the greenest pastures, the low plains in winter, and the high valleys in summer. All the ancient routes that have witnessed encounters and exchanges in all the dialects of the ‘umbrella language’ of Provençal. So it is with the transhumance routes of translation, the slow and patient crossing of countries, all borders eradicated, the movement of huge flocks of words through all the vernaculars of the umbrella language of poetry.

Te \Hanh, transported by writing that was both so foreign and yet so infinitely familiar, read with wonderment Char’s dedications to him, steeped in the scents of Les Busclats. Char’s poem emerged from this great journey into Vietnamese as if it had been hewn from the earth of the rice fields.

Translation and poetry, a far-off encounter at the confines of language, on the watershed, the essence of hospitality.

H: Thank you for this wonderful conversation. It was so enjoyable. Thank you for your time. Thank you very much.

Ros Schwartz: Thank you for your time and thank you for inviting me.

* For your Valuable feedback on this Episode – Please click the link below.

https://harshaneeyam.captivate.fm/feedback

Harshaneeyam on Spotify App –https://harshaneeyam.captivate.fm/onspot

Harshaneeyam on Apple App – https://harshaneeyam.captivate.fm/onapple

*Contact us – harshaneeyam@gmail.com

***Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by Interviewees in interviews conducted by Harshaneeyam Podcast are those of the Interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Harshaneeyam Podcast. Any content provided by Interviewees is of their opinion and is not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, individual, or anyone or anything.

Leave a Reply